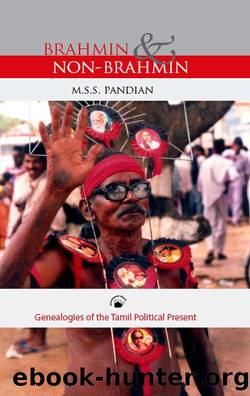

Brahmin and Non-Brahmin: Genealogies of the Tamil Political Present by M.S.S.Pandian

Author:M.S.S.Pandian [M.S.S.Pandian]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9788178243597

Publisher: Orient BlackSwan Private Ltd.

Published: 2018-06-25T18:30:00+00:00

CONVENTIONS OF POLITICS AND THE JUSTICE PARTY

Before analysing how the Justice Party produced a new redescription of the Brahmin and gave rise to a new non-Brahmin common sense, let us examine how the norms and conventions of formal politics authorized by the colonial state informed political activity generally as well as the activities of the Justice Party.

Ian Hacking, in his illuminating work on how probabilistic regularities emerged as a major explanatory scheme in Europe, characterizes early-nineteenth-century European society as âstatisticalâ.22 While Hacking builds on the âavalanche of numbersâ which flooded Europe at this time to provide us a fascinating story of how probabilistic reasoning shaped a new way of looking at the world, the work of Mary Poovey shows the complex processes during the preceding three centuries which invested numbers with cultural authority. 23 Going through the epistemological careers of diverse projects such as the emergence of rule-governed mercantilist writing and the decline of rhetoric, Baconian natural philosophy and Scottish conjectural history, she establishes how numbers, in early-nineteenth- century Britain, gained connotations of transparency and impartiality and became the basis for systematic knowledge. With the emphasis now being on âdisinterestedâ knowledge, numbersâ because discrete and deracinatedâwere treated as the foundations of such knowledge.

British colonialism, in keeping with governmental practices in the home country,24 produced incredible amounts of numerical data on varied aspects of the population in British India. The success of Benthamite Utilitarianism as the basis for colonial administrationâ an idea shaped by James Mill, T.B. Macaulay, J. Fitzjames Stephen and othersâreinforced this statistical imagination.25 In other words, Benthamâs principles of publicity (transparency of public dealings) and inspectability necessitated the collection of such data. For example, referring to â[t]he highly organized system of regular reports and the collation of all kinds of statisticsâ by the Punjab administration, Eric Stokes notes: âThey represent precisely that form of inspection and control which Bentham had suggested in his Constitutional Code as the proper safeguard against the dangers of concentration of authority in individual officers.â26

These statistical enquiries were not viewed by Indians as tools of impartiality and transparency, but rather as informed by the coercive intentions of colonial rule. For example, referring to the Indian census operation in Punjab, Denzil Ibbetson noted:

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

Born to Run: by Christopher McDougall(7127)

The Leavers by Lisa Ko(6948)

iGen by Jean M. Twenge(5416)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(5372)

Spare by Prince Harry The Duke of Sussex(5197)

The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini(5180)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4313)

Bullshit Jobs by David Graeber(4190)

Never by Ken Follett(3957)

Goodbye Paradise(3810)

Livewired by David Eagleman(3775)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(3399)

A Dictionary of Sociology by Unknown(3085)

Harry Potter 4 - Harry Potter and The Goblet of Fire by J.K.Rowling(3074)

The Social Psychology of Inequality by Unknown(3031)

The Club by A.L. Brooks(2925)

Will by Will Smith(2920)

0041152001443424520 .pdf by Unknown(2846)

People of the Earth: An Introduction to World Prehistory by Dr. Brian Fagan & Nadia Durrani(2738)